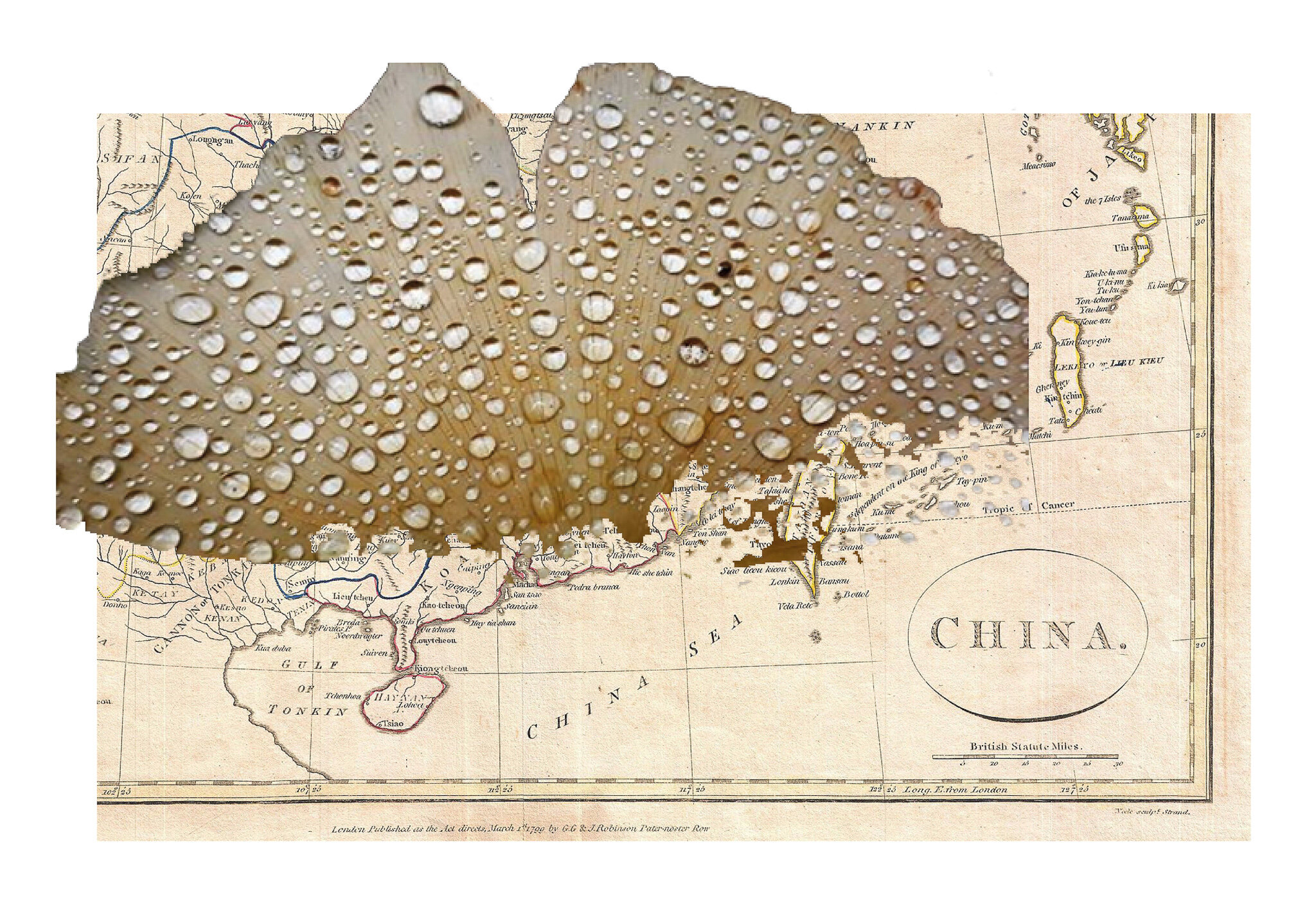

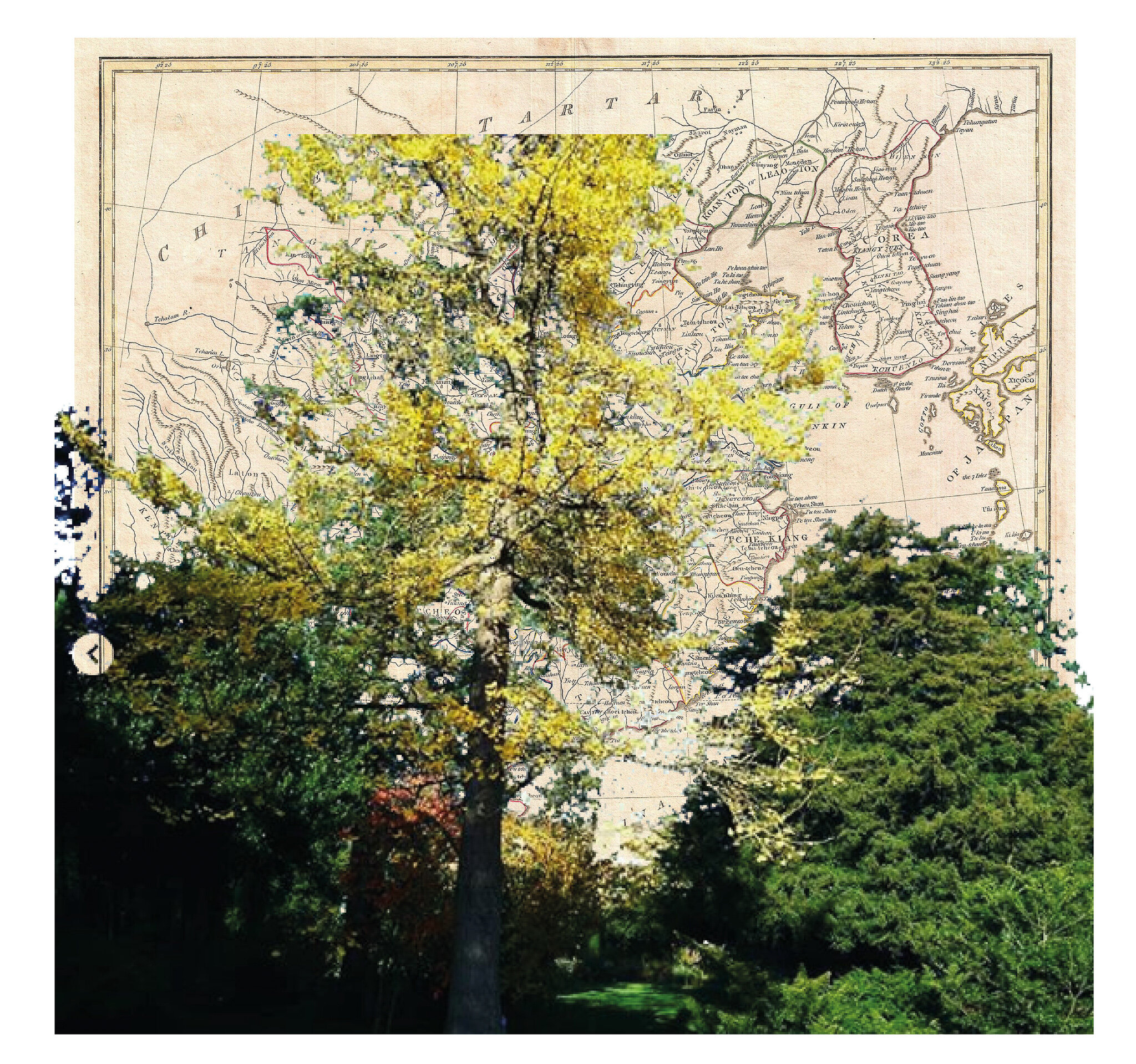

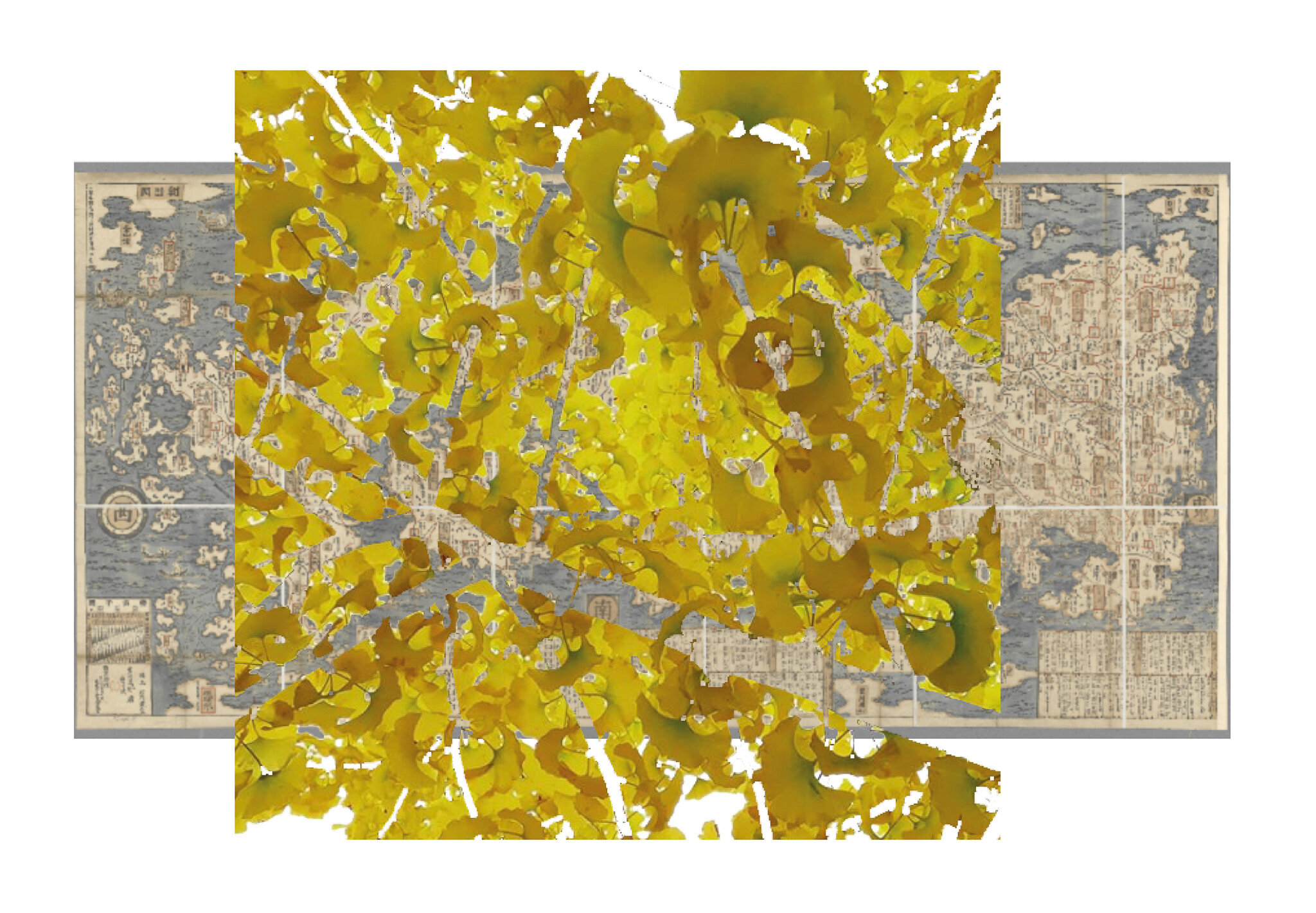

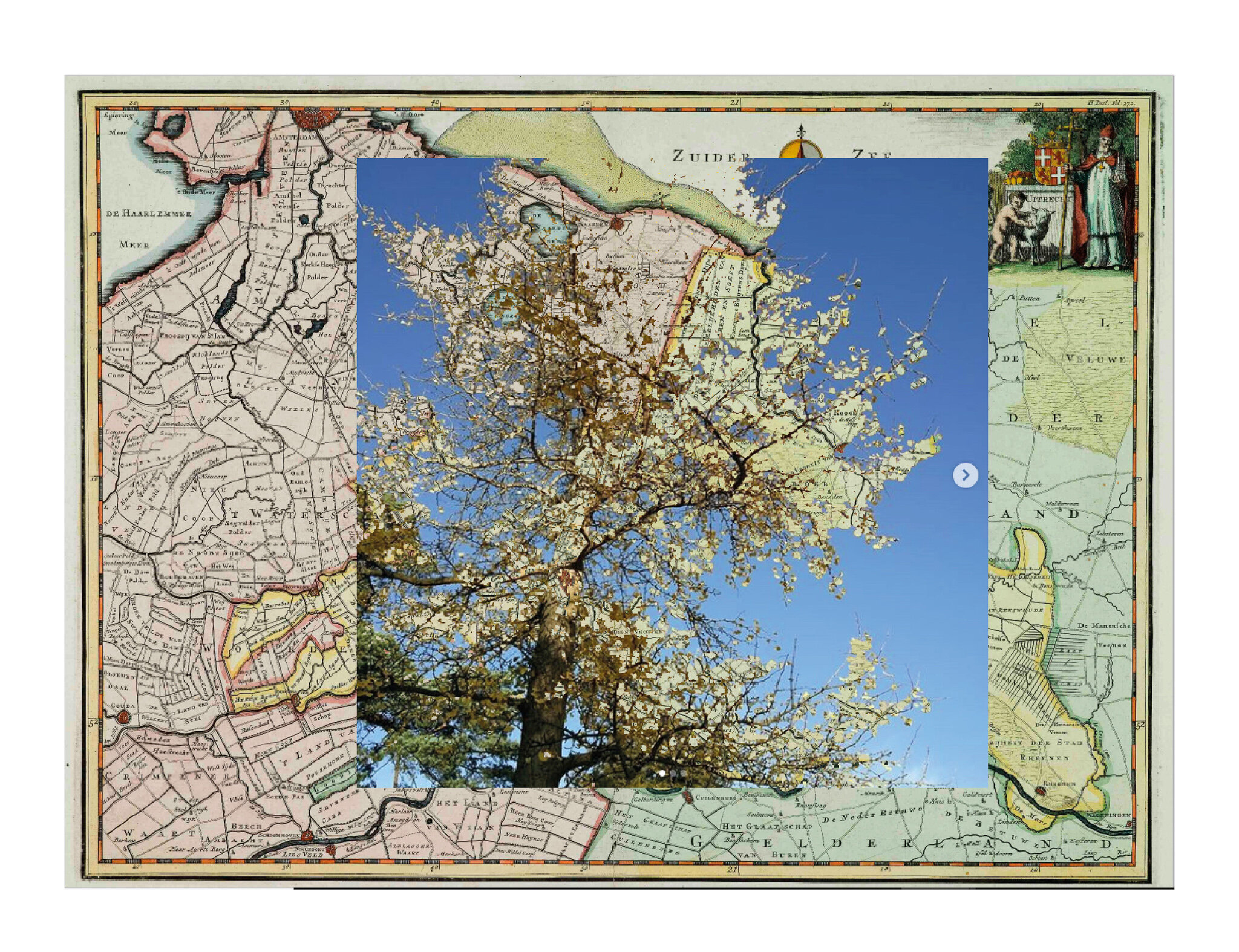

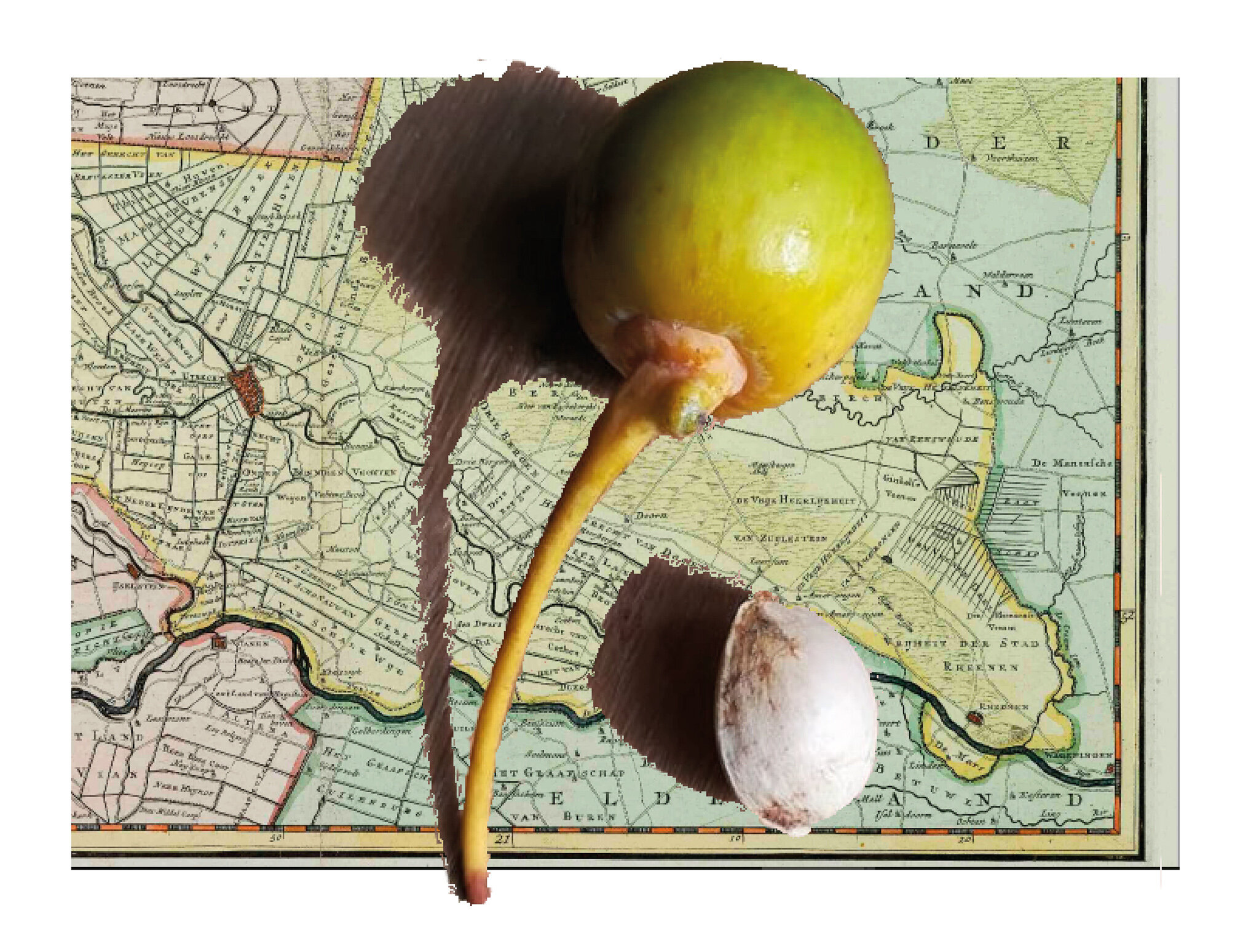

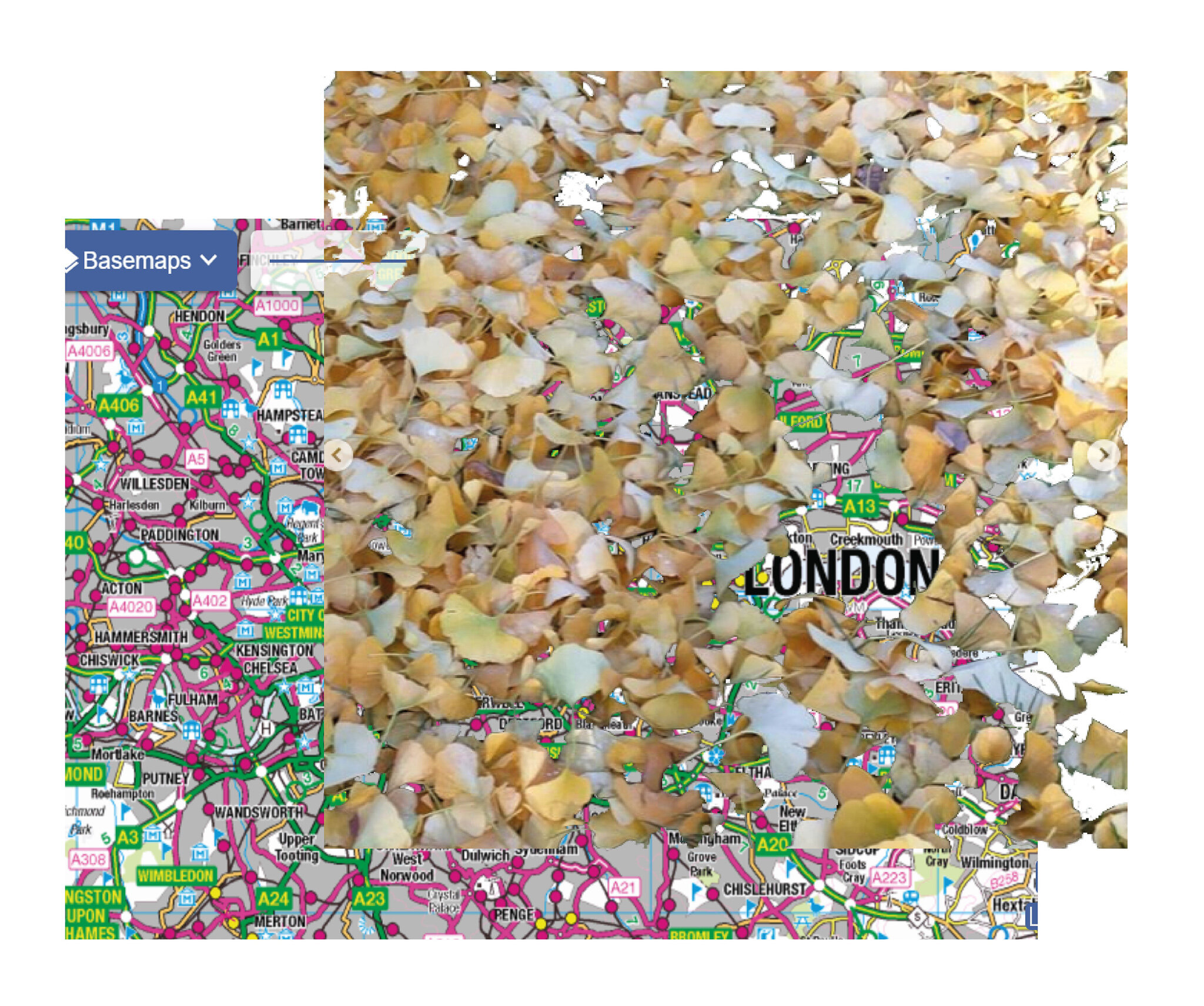

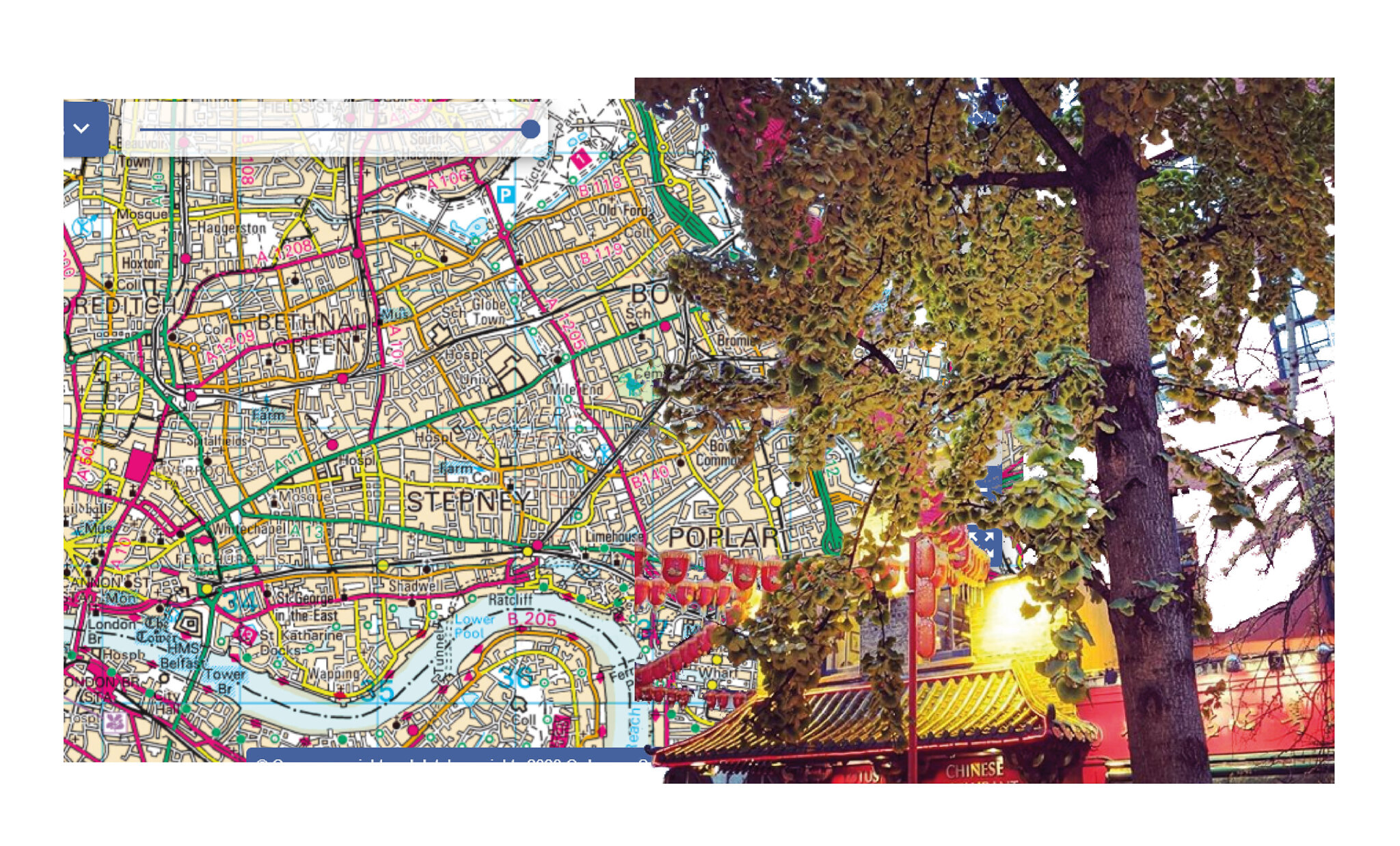

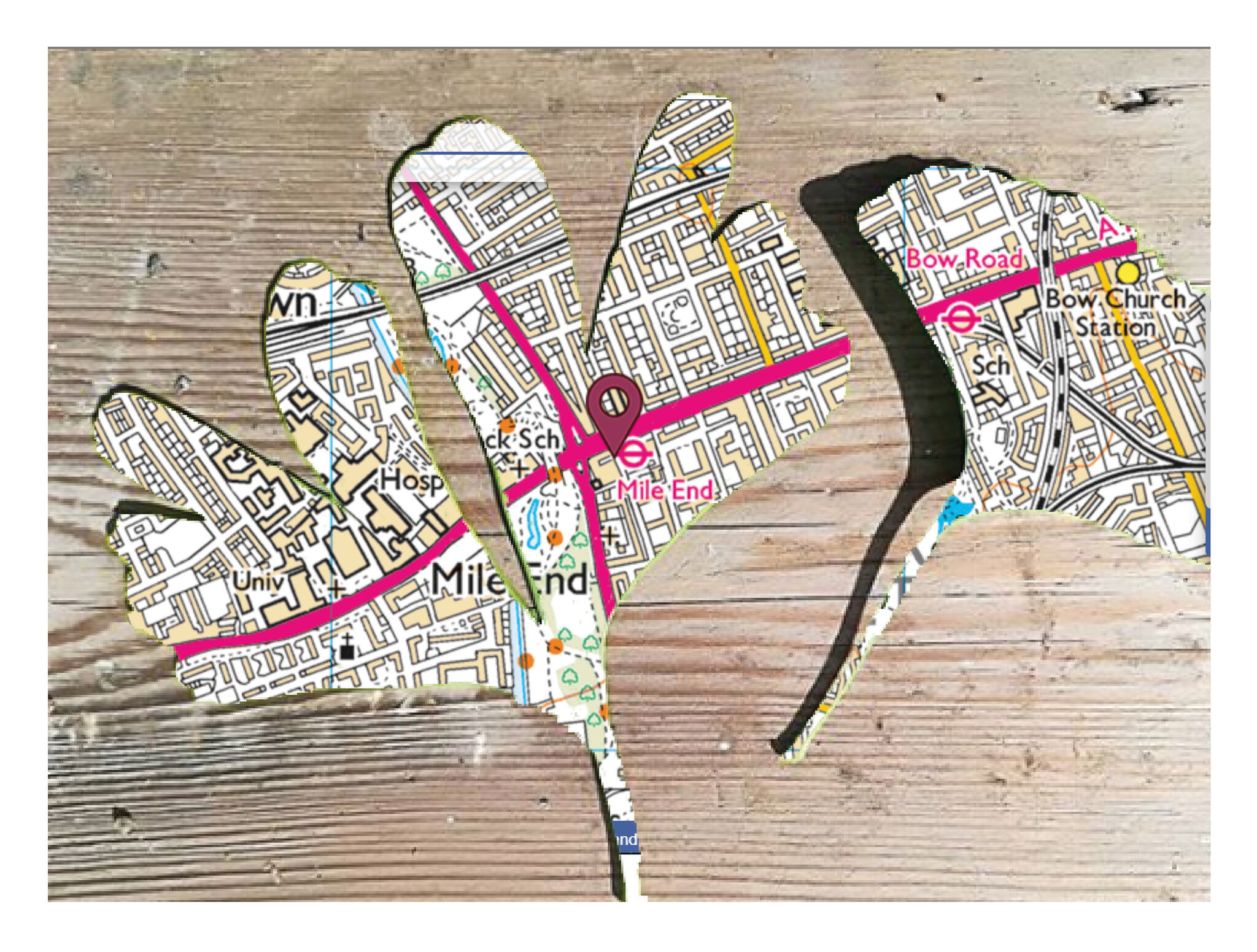

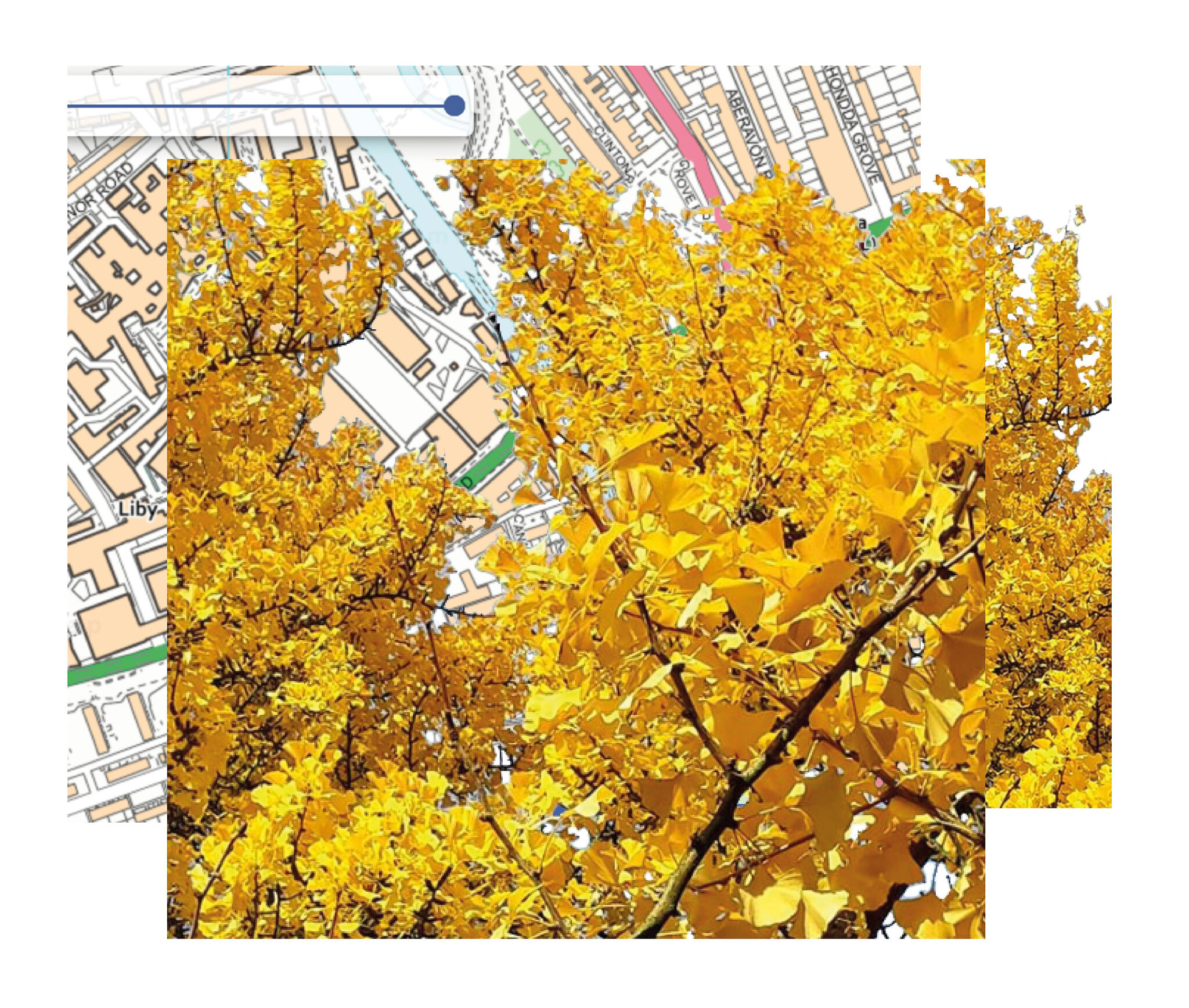

#Ginkgos of the British Isles is an academic research project that invited anyone on Instagram to share photos of specimens of the popular tree ginkgo biloba spotted anywhere in the British Isles. These photos have been paired with selected map images, relating to ginkgo biloba’s journey to the British Isles – from China, via Japan and the Netherlands, to the east end of London in 1750.

The Collages

The National Collection

The National Collection of Ginkgo biloba and Cultivars is maintained by Tony Davies in Worcestershire. It currently holds over 225 cultivars, the majority of which are currently living in ‘Air-pots’ so that they can develop healthy root systems before being planted in the ground in future. Find out more about the The National Collection of Ginkgo biloba and Cultivars here.

National Collections of garden plants are registered and documented groups of garden plants, often maintained by enthusiasts as well as by professional gardeners in gardens open to the public. Find out more about National Collections here.

ABOUT THE RESEARCH

#ginkgosofthebritishisles is a visual research project by Dr Claire Reddleman, in the Dept of Digital Humanities, King’s College London. I received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Institute at King’s College London. The project aimed at testing out the possibilities for using Instagram as a way to crowd-source photographs of ginkgo biloba trees, in order to bring them together with maps, to create a sort of co-produced view of how this particular introduced species is experienced as part of the visual life of the British Isles. All images contributed to the project hashtag are displayed here, paired with map images of the species’ places of origin, including Japan where the tree was ‘discovered’ by the German surgeon and traveler Engelbert Kaempfer in 1692, China where the species is native, and Mile End, London, where the first seedling in Britain was raised in 1750.

This project represents a new departure for me in terms of methods, and extends existing research interests that I have been developing through recent postdoctoral research, as well as independent creative work. In previous research, particularly my book Cartographic Abstraction in Contemporary Art: Seeing with Maps and an article Disrupting the cartographic view from nowhere: ‘hating empire properly’ in Layla Curtis’s cartographic collage ‘The Thames’ I have explored how artworks that engage with maps and mapping techniques can shed light on how maps position us as viewers and foster relationships with the world that enable us to gain knowledge as well as to mediate power relations. I have written about maps as demonstrating certain aspects of artistic collage techniques, and the trope of collage as a method for combining disparate elements into a new whole is one that I intend to keep exploring in new ways.

This research links with my broader interest in visual culture, and my artistic practice as a photographer. I have previously exhibited collaborative, collage-based photographic work looking at the idea of trees in everyday life and how we perceive them. I have taken these interests forward in recent postdoctoral work exploring how French penal colonies have been mapped and photographed, historically as well as in the contemporary context of penal heritage and associated tourism. As part of this project, led by Dr Sophie Fuggle, I created a digital photographic archive of former penal sites, as well as collecting plant samples and soil samples for use in original artistic collages involving photography and cartography of the penal colonies. This engagement with plants and the politics of whether plants are classified as native or non-native prompted me to develop a much larger research idea, ‘Planting the Nation’. This explores how the history of British plant introduction could be engaged with using visual methods, in order to contribute to a future imaginary of Britain as a global place that is materially constituted (in part) through plant introduction. Many introduced plants have become garden favourites, and I am keen to explore whether people’s feelings and opinions about multiculturalism can be affected by greater understanding of those plants’ histories. This is too large a project to embark on at this stage of my career, so I am keen to develop projects that could contribute to my having a better understanding of what research methods will best serve my research interests, and best facilitate participation using visual methods.

I have previously used social media (Twitter and Instagram) as dissemination tools, but I have not yet tried to use it as a participatory research method. I am keen to experiment with using Instagram as a participatory research tool as it prioritises photography and it has developed large audiences interested in plants, horticulture, and amateur and professional plant photography.

Alongside using a new method for participatory research, I am contributing my own photography to the project through visiting the National Collection of ginkgo biloba and cultivars which is housed at Evesham, Worcestershire. I have also commissioned a response of c.1000 words to the online project, to be written by an academic in the fields of cultural geography, ecocriticism or botany. This is, again, a new technique for me, and I think it could add a valuable perspective for website visitors, as well as providing an avenue for me to develop further relationships with other researchers who share this interest, potentially leading to future directions in which to take this research.

Research questions

1. Can visual approaches to the history of plant introductions to the British Isles help to develop an imaginary of Britain as an island place that is constituted from global sources?

2. Can focusing in on one species offer a useful way of engaging this complex history, which is vast and includes multiple academic disciplines such as botany, environmental sciences, history, travel narratives, botanical history, etc.?

3. Can Instagram function as a helpful research device, enabling potentially hundreds of people to participate by contributing photographs to the project Instagram hashtag?

4. Can photography and cartographic images be brought together in an online presentation, in order both to stimulate interest in the geographical relationships embodied in the chosen plant species, and to explore further the ways of viewing the world that photography and cartography make possible?

A note on naming

At this moment in the cultural and political life of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (at the time of writing in 2019), it is not entirely straightforward to refer to this group of islands by name. I have opted for ‘British Isles’ because I think it will be more widely recognised than other alternatives, such as ‘British Archipelago’ (meaning group of islands), while still emphasising the character of this place as a collection of islands.

I have chosen not to use ‘Great Britain’ because that name doesn’t include Northern Ireland; and because Northern Ireland is part of the UK, I am curious about the presence of ginkgo biloba there, and in the whole island of Ireland. The political entity into which ginkgo biloba was introduced in London in 1750 was known as the ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’, incorporating the then ‘Kingdom of Scotland’ and the ‘Kingdom of England’ which included Wales. Since 1750, ginkgo biloba has been widely planted as a street tree and has a presence at least as far south as London, as far north as North Queensferry, and is widely available in garden centres in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (which I take to mean it is being planted in private gardens). I hope this project will offer a way to gather a picture of ginkgo biloba across the whole of these islands in 2019.

Transplantation: A response in fragments to Claire Reddleman’s ‘Ginkgos of the British Isles’

Jan van Duppen, 2021

A while ago, Claire Reddleman invited me to respond to her research project Ginkgos of the British Isles, which invited a distributed collective effort in documenting Ginkgo trees as part of everyday living environments. Reddleman set out a call and invited the public to contribute pictures of Ginkgos through the social media platform Instagram. The project engages with the complex history of this particular species and hopes, in her words, to ‘develop an imaginary of Britain as an island place that is constituted from global sources’. She worked with the generated Instagram feed of Ginkgo pictures and translated this small collective archive into collages—layering and reinserting historical maps that trace the species’ trajectory from China to the British Isles. This return to historical maps could have the danger of performing a nostalgia for a lost Empire, it might have fixed these trees back into historical trajectories of colonialism, exploitation, and racism. Yet, these trappings appear to have been avoided as the crowd-sourced contemporary photographs of Ginkgo trees pierce through these historical maps, they disrupt the reduced representations of territories of empire. The collages escape the framings of the map, a Ginkgo tree leaf full of dew wets the paper, a map of London takes the shape of a Ginkgo leaf, these sorts of translations help to complicate our understanding of the temporal and spatial trajectories of this species. My response to Ginkgos of the British Isles has been simmering at the back of my mind whilst work obligations took over and the pandemic struck, I started to notice Ginkgos on my walks in London and followed the project’s progress on Instagram. Instead of writing up a cohesive linear text, I found it would be most appropriate to respond in fragments to Reddleman’s project. The quotations and images included here crossed my path whilst thinking through its collages. I invite the reader to loiter amongst these fragments as they might help to question the multiple transplantations of the Ginkgo tree.

Young Ginkgo Tree Leaf, 20 June 2021, Bloomsbury - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

verpFlanzen

‘Übersetzen signifies “translation” in the Latin sense of traducere, “to lead across.” “To translate” is to bring a discourse across from one language into another, that is to say, to insert it into a different milieu, a different culture. Translation is not to be understood as a simple “transfer” or as a pure linguistic “version,” but instead within the general development of the spirit. This idea, already present in Luther, would be taken up by Goethe, Herder and Novalis, and in a general way by the first romantics that considered this exchange between languages as the condition of Bilduing (Berman, The Experience of the Foreign). Schleiermacher’s theory of the methods of translation, which favours the reader’s encounter with the foreign, is likewise completely based on the analysis of this movement. “Translation” is thus considered as a “transplantation”: to translate is “to transplant [verpflanzen] to a foreign soil the products of a language in the domains of the sciences and the arts of discourse, in order to enlarge the scope of action of these products of the mind” (“Über die verschiednen Methoden”)’ (Auvray-Assayas et al. 2014, p. 1150).

a culture not of roots but of routes

‘The predominant academic conception I’d initially inherited envisaged cultures as settled, stable, traditional, and continuous with their origins: what we would call a ‘roots’ conception. Paul Gilrloy, particularly, criticized this as generating a mode of thought which he believed carried with it an inevitable commitment to a cultural or an ethnic absolutism. This critique made it possible to reimagine cultures as what James Clifford and others designated ‘travelling’ ones: cultures ‘on the move’, constantly reconfigured through ‘discovery’, conquest, migration, adaptation, enforced assimilation, resistance and translation. In other words, a culture not of ‘roots’ but of ‘routes’, which invites a mode of interpretation which I have been designating here as diasporic’(Hall and Schwarz 2018, pp. 75–76).

exhale, inhale

‘Street trees are central characters in narratives about urban health. Often the only living element on a street, trees indicate a neighbourhood’s vitality. While an abundant canopy of lush, robust, and long-living trees conjures associations of health, safety, and quality of civic life, a sparse, broken, dying canopy instead reflects disinvestment, social decay, and disease. These associations are both ideological and real. On the one hand, as living organisms, trees in the city have long symbolized an implant of “nature”; they are seen as a natural salve – die or thrive based on investment and maintenance; they register the systemic and spatial inequalities that exist within the city. When they flourish, they improve the air that people breathe in, the very stuff of human survival. As trees exhale, humans inhale’ (Hutton 2013, pp. 148–149).

illicit pickings

‘Despite the bioculturally diverse conditions supporting foraging in Seattle, institutional regulations, land-use policies, and urban greenspace management practices often specify which plants can go where, who may engage with them, and how’ (McLain, Hurley, Emery, and Poe 2013). ‘‘Species status’ is a central concept, one drawn from the concerns of conservation science, guiding urban green space management. The concept has given rise to a robust and rather expansive network comprised of humans, technologies, and ideologies dedicated to the removal of ‘alien invasives’ as well as reintroduction and maintenance of particular suites of ‘native species’ (Green Seattle Partnership 2012; Ramsay et al. 2004). In addition to influencing species assemblages, urban managers also influence how people interact with plants and mushrooms in the city. For example, when city horticulturalists plant non-fruiting cultivars, picking fruits and nuts from city trees such as cherry, plum, and ginkgo is clearly not intended and moreover, is rendered impossible. Furthermore, urban managers normalize certain nature practices through Seattle’s municipal code, which prohibits the removal of plants and plant parts from city parks without authorization. Yet, city park officials and volunteer restoration groups go to considerable effort and expense to remove Himalayan blackberry and other forageable species (e.g., knotweed, holly, garlic mustard), altering the use potential of existing urban spaces and creating an inherent management contradiction to the blanket prohibition against removing plants’(Poe et al. 2014, pp. 6–7).

‘Ginkgo Health & Beauty’, 23 March 2021, Fitzrovia - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

gleaning

‘Above all, as a fugitive of Europe’s landscaping practices, Ailanthus requires us to sharpen our peripheral vision: emerging by chance, these trees easily escape structured observation. You never know exactly where to find them. An analytic that tracks ruderal ecologies in the city can therefore cultivate modes of attention that utilize chance and gleaning as a practice of social inquiry rather than focusing on bounded units, predictable political economies, and coherency’ (Stoetzer 2020, p. 88).

embrace

‘The Ginkgo grows at the south west corner of the Garden, its thick trunk and meandering branches render visible the wise old age of this living fossil. The tree is subject to its own transformations, seasons and cycles and exists in relation to three centuries of Europe’s Social Histories. I walk up to the tree’s large trunk and embrace its resilient form. Around me, cover crops shoot shallow roots into the earth. English ivy winds its way through the foliage and fixates itself onto the ginkgo, meandering upwards. A moist climate and wet weather conditions invite green moss and lichen to take refuge on the ginkgo’s woody exterior. Large entangled forms of the tree’s thick trunk spiral and branch outward to catch the sun’s rays. Steel wires tie together the most precarious of branches to decrease probability of the tree breaking in a storm. From the steel bands, I trace the outlines of one peculiar branch. From it, hangs a bushel of ginkgo seeds, hundreds of them’(Pekal 2020, p. 36).

resilient

‘However, despite these shortcomings, Sommer’s and his student’s work ultimately facilitated the revitalization of the tree canopy in Dresden. The renewed attention paid to street tree planting in the city also inspired nurseries to cultivate resilient species that could resist many of the shortcomings of urban environments, such as Tilia tomentosa, Sophora japonica, Platanus x hispanica, Ginkgo biloba, Corylus colurna, Sorbus latifolia, and Sorbus intermedia, as well as several species with small tree crowns that could be planted in narrow streets’ (Dümpelmann 2020, p. 95).

Young Ginkgo Tree, 20 June 2021, Bloomsbury - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

social uproar

‘The ginkgo tree was brought to Estonia at the end of the 19th century as an exemplar of a taxonomically and evolutionarily rare species. The tree carried also connotations in terms of the cultural space which it embodied and symbolized – this particular specimen originated from Germany and was associated with German culture through associations with J. W. von Goethe and his time, but also through the German roots of gardening in the Baltic provinces. When the tree was drawn into the centre of social uproar in the 1980s, it had been “domesticated” as part of the local milieu and cultural memory of Estonians, while the foreign origin of the species and the specimen was pushed to the margins of cultural memory. This demonstrates that changes in cultural memory can go hand in hand with changes in the delimitation of cultural space and vice versa, and non-human organisms which share their living space with humans may acquire a metonymic significance once they are perceived as an integral part of a certain valued environment’ (Magnus and Sander 2019, pp. 250–251).

medicinal

‘In many countries such as France, the USA, and China, plantations have been established to cultivate G. biloba for the supply of ginkgo leaves to the pharmaceutical industry. Application of biotechnology through tissue culture and genetic engineering are choice approaches for conservation of the species and to meet industrial raw material demands for production of ginkgo herbal supplements. The low yield of ginkgolides and bilobalides and the slow growth of the tree along with low yield of the compounds in undifferentiated tissue are impediments to the supply of the compounds, especially the ginkgolide B that shows promise as highly antagonist against platelet-activating factor, which is involved in the development of many respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, and central nervous system disorders’ (Isah 2015, p. 146).

orientalism

‘For their exhibition at the Biennale, Gilbert & George created a completely new group of large 25 pictures using an advanced computer technology that they had spent two years perfecting. Entitled Gingko Pictures, the new works used leaves from Ginkgo biloba trees collected from a park in New York as both a point of departure and recurring motif. This particular species of tree, Ginkgo, was carefully selected as it is no longer rare and the trees can nowadays be found in avenues, parks and even in the streets close Gilbert & George’s home in east London. Ginkgo is revered in the Far East, where it is associated with longevity and reputed to have miraculous powers. These extraordinary properties act as a metaphor for the spirit that runs throughout the 25 pictures. The predominance of the rich golden yellow in many of the pictures is synonymous with the colour the leaves turn in the autumn months. Gilbert & George’s Pavilion installation featured some recurring themes that make their work and visual language so distinctive: symmetry, mirroring, bold colours and large grids’ (British Council 2005).

references

Auvray-Assayas, C., Bernier, C., Cassin, B., Paul, A., and Rosier-Catach, I., 2014. To Translate. In: B. Cassin, ed. Dictionary of Untranslatables - A Philosohical Lexicon. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1139–1155.

British Council, 2005. Ginkgo Pictures by Gilbert & George - British Pavilion Venice Biennale [online]. Available from: https://venicebiennale.britishcouncil.org/history/2000s/2005-gilbert-george [Accessed 1 Sep 2021].

Dümpelmann, S., 2020. Seeing, surveying, and sorting urban trees: the 1970s street tree project in Dresden. In: M. Gandy and S. Jasper, eds. The Botanical City. Berlin: jovis Verlag GmbH, 91–99.

Hall, S. and Schwarz, B., 2018. Familiar Stranger. London: Penguin Books.

Hutton, J., 2013. Reciprocal landscapes: Material portraits in New York City and elsewhere. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 8 (1), 40–47.

Isah, T., 2015. Rethinking Ginkgo biloba L.: Medicinal uses and conservation. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 9 (18), 140–148.

Magnus, R. and Sander, H., 2019. Urban trees as social triggers: The case of the Ginkgo biloba specimen in Tallinn, Estonia. Sign Systems Studies, 47 (1–2), 234–256.

Pekal, A., 2020. Assembling the Natureculture Garden: A Diffractive Ethnography of the Utrecht Oude Hortus. Utrecht University: Master Thesis.

Poe, M.R., LeCompte, J., McLain, R., and Hurley, P., 2014. Urban foraging and the relational ecologies of belonging. Social & Cultural Geography, 15 (April), 1–19.

Stoetzer, B., 2020. Ailanthus altissima, or the botanical afterlives of European power. In: M. Gandy and S. Jasper, eds. The Botanical City. Berlin: jovis Verlag GmbH, 82–90.